We Can Predict Who Will Need Home Care – But Should We?

Update: Get the research paper in the Journal of the Royal Statistical Society as of January 2021

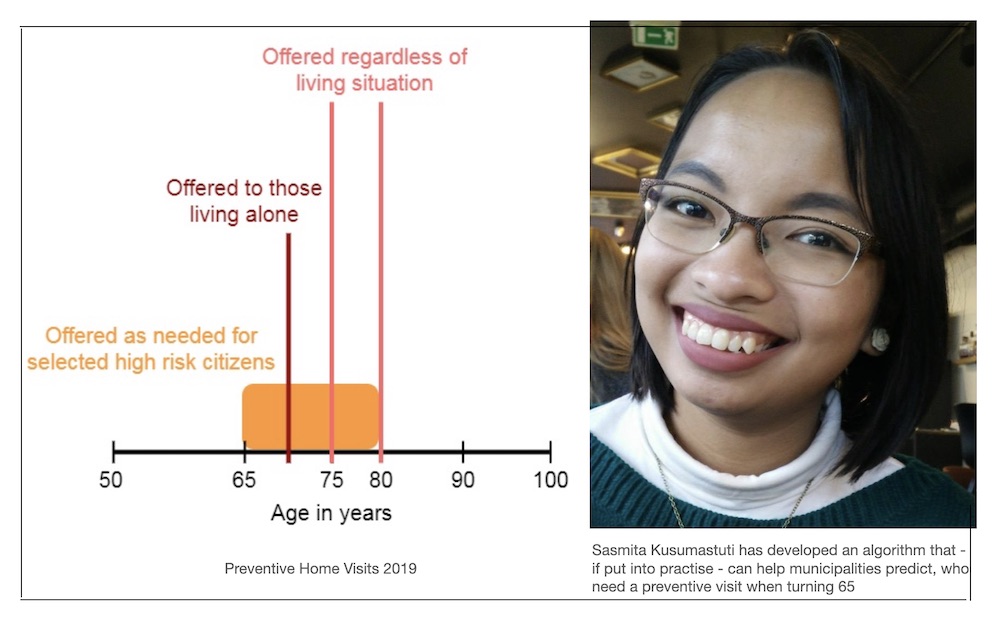

Interview. In Denmark, when you turn 65, you’re supposed to get a visit from the municipality if you need it. The purpose is to assess your living situation and find out if you need any help, be it home care or preventive programs from the public authorities. When you turn 75 (70 if you live alone) you get the visit no matter what, but at 65 you will have to need it. But how will a municipality know that you need it? It is very expensive to send out a municipality officer to every home of a person, who has just celebrated their 65 years birthday. And with the perspective of fewer public resources and a growing elder population, it gets even harder.

Could data and machine learning help here? Sasmita Kusumastuti, an assistant professor at the Section of Epidemiology, Department of Public Health and Center for Healthy Aging at the University of Copenhagen, believes so.

“In my project we have proven that we can use data and machine learning to develop a predictive algorithm to help the municipality identify, who will be most prone to needing homecare,” she says. “The end goal is of course to help more citizens by making preventive care more sustainable and cheaper in the long run.”

Anonymized register data from Statistics Denmark, health data from Sundhedsdatastyrelsen and data from Copenhagen Municipality are the ingredients in the predictive algorithm. No data derives directly from patients. It is data such as living situation education, family structure and economic status, whether you have been hospitalized, diagnoses and medicine intake, and what kind of care has been received. Data goes back over 15 years.

“We study the patterns of events in your life. For example a male, age 75 with high social and economic status, who was hospitalized some years ago, may be due to a broken hip, and he has maybe received some medications. All these patterns are used in our predictions which may end up saying that there is 80% risk of needing home care in the near future for a person with these characteristics,” explains Kusumastuti.

The project also looks at historic data on those who already received home care to assess common characteristics which make people prone to needing homecare.

This could be implemented in a way that when you turn 65, and the algorithm shows that you have a 60% or higher risk of needing home care in the coming years, then you will be offered to be visited by the municipality, she explains. She says that the algorithm developed in collaboration with machine learning experts has a pretty good accuracy.

“We made a prediction on over one million older citizens on historic anonymized data. We had a learning period between 1997 and 2014, where we analyzed the sequence of events or patterns in your life e.g. moving to a new place, getting a divorced, living alone, being hospitalized, taking medications etc. Using this information, we predicted who would need home care at least one hour a month or admitted to nursing home, and we landed at an accuracy between 85 and 95 percent,” she says.

The algorithm for now is only used for research and has not been implemented for real life. Today, the municipality make decisions on who needs home care and how much care based on questionaries they have to fill out for every preventive home visit. They definitely visit you, when you turn 75 (70 if living alone), if you say yes to the offer. There has been some reports that some citizens or residents that are ethnically not Danish said no to the home visit offer, but most say yes. But it is very hard to find out who are in need at 65 and thus hard for a municipality to live up to the promises of the welfare law and optimize their prevention strategies.

Many Ethical Aspects

Sasmita Kusumastuti is very aware of the controversial aspects of her project.

“Like a knife or any kind of tool, whether it is good or bad depends on the one operating the tool. Therefore, we need to call attention to data ethics to prevent chaos. We have to ask ourselves: What is right, just, and appropriate,” she tells Danish IT.

Among the ethical questions, that Sasmita is asking herself, are:

- Who is this benefitting most: The most vulnerable citizens who get a visit and thus receive prevention programs or home care in time or the municipality who can save money or use the money for something else. To be data ethical it has to foremost benefit the human being.

- Are there any bias in the algorithm favoring e.g. old Danes over new Danes? According to Kusumastuti, register data does not systematically exclude anyone, and register data is enough to make predictions. If one is new in Denmark, for example 5 years, then there is not so much data that the algorithm can predict on, so in that sense it is more difficult to predict newcomers. On top of that, there is only data on those accepting the offer of the visit. There fore we do not have information on those who was offered but declined the visit. Hence what we are doing is predicting the use of care, and not the need of care.

- Fairness. Is this predictive algorithm in any way the same as predicting whether someone will commit crime, she asks, noting that we are predicting who are most likely to be a burden to society in their senior life.

- Equality. And finally, are we leaving somebody out? This is definitely happening today without the use of data and machine learning, but will it become better with use of data and machine learning?

In some ways data is not the same as reality, it does not tell the whole story, and it is not good enough without corrections. For example register data only shows where you live and if you live with somebody. It does not show if you have relatives living nearby who could help you, she explains. Researchers also lack behavioral data e.g. smoking, drinking, exercise habits that is very influential in healthy ageing.

Apart from the ethical considerations, there are two things that need to be put into place, if the predictive algorithm should be used for real.

“Municipalities don’t have access to register data at Statistics Denmark. I have as a researcher. And secondly, you need to get citizens’ consent to run any predictive risk algorithm on personal data,” says Sasmita Kusumastuti.